Unhappy Birthday

We’ve all seen it. We’ve all heard it. We’ve all scratched our heads in confusion. Restaurant staff bring out a birthday dessert and sing... what in the world is that? Oh, I heard “birthday” in there. Is that a birthday song? Why not sing the birthday song, “Happy Birthday to You,” like the rest of the world?

Because it was under copyright! And the copyright holders were charging $700 per use! Unsurprisingly, many people wanting to use that song in a professional setting decided to come up with their own birthday song rather than pad the pockets of Warner Chappell Music. This is a subsidiary of Warner Music Group, a former subsidiary of WarnerMedia, formerly known as AOL Time Warner, soon to be known as Warner Bros. Discovery... in a nutshell, a very large corporation that even Kevin Bacon would have a hard time connecting to the song’s roots. It was originally written by a schoolteacher and her musician sister in the late 19th century, possibly basing it on popular ditties from the middle of that century. In 2015, over a hundred years after its creation, the song was ruled public domain in the United States because a judge finally noticed that one of the intermediary companies involved had based their copyright claim on specific piano arrangements and new verses rather than on the original lyrics and melody. AOL Time Warner Music Media Chappell Company Incorporated Discovery Whatever was ordered to pay back the last $14 million of collected royalties (about seven years’ worth of royalty income for that song).

That mess is the tip of the iceberg, and you can thank Disney for it.

The Mouse’s house is his castle

Small, independent creators – authors of esoteric textbooks, a few friends making a video game together, struggling artists – usually hold very straightfoward expectations about their work, considering it a success if they can make a comfortable living while receiving recognition and praise for their efforts, just like any teacher, welder, doctor, or assistant manager. That’s the ideal use case for a copyright system, allowing talented creators to do exactly that. Before 1976, this goal was the foundation of copyright law. In 1790, a copyright term lasted 14 years, with an option to renew it for another 14. In 1831, the initial term was increased to 28 years, and in 1909, the renewal term was increased to 28 as well. Unfortunately for literally everyone, some people were not content with laws made for human beings. These people were, ironically, also human beings, but they were being paid by something that isn’t a human being: a corporation.

And that corporation is Disney.

Corporations, you see, are immortal and eternal; the cliché advice “you can’t take it with you” doesn’t apply to entities that can potentially live forever. Since they’re not going anywhere, they have good reason to accumulate wealth – in fact, that is a for-profit corporation’s only purpose: to make as much money as possible, all the money, all the time. Thus, they don’t just want to make a living like you and I; they benefit from as long of a copyright term as possible. Disney has been lobbying for just that for decades. In 1976, that 56-year maximum turned into 50 years past an individual author’s death or 75 years past the publication of other works (including corporate holdings). Today, it’s 70 years past an individual author’s death, and other/corporate works fall out of copyright either 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, whichever comes first.

Basically, Disney didn’t want to take the chance that anyone else might conceivably make money from Mickey Mouse, as Steamboat Willie (the first short featuring Mickey) would’ve entered public domain in 1984 under pre-1976 laws. This includes, for example, painting the walls of a daycare center with the public face of the happiest place on Earth without prior authorization or licensing. Yes, Disney came close to suing three daycare centers. You see, the kids might have a better time at a daycare center where they can see Mickey, which would make their parents more likely to select such a facility, which is money, therefore you’ll be hearing from our lawyers, you pirate scumbags. All three businesses gave way under the threat of legal action and painted over those murals with characters from Universal Studios and Hanna-Barbera, which had gotten wind of the situation and didn’t waste any time arranging free licenses for what was effectively targeted advertising to a captive audience. Now, it is true that businesses are legally required to protect their intellectual property (IP) or courts may rule that it’s been abandoned (elevators are one example of this process, called genericization). But why not work together and work out a license agreement instead of letting some other entertainment company jump in?

Because Disney.

Is our children learning?

Sure, but it depends on how much money their teacher wants to spend.

Unsettlingly, Disney’s interference is thrown into painfully sharpest relief not with Disney properties per se but with everything else. Disney meddled lobbied fairly. They didn’t demand different treatment from other IP holders. So, with the blind equilibrium of the scales of Justice, these copyright laws apply to every copyright holder. You have to go back nearly a century for free characters to paint on the walls of your daycare center. Your alternative is to iron out a contract with a copyright holder, which is almost certain to cost more than the actual paint job after licensing fees and lawyers’ fees (unless your firm’s general counsel works for free because he’s your wife’s cousin Kevin who is a lawyer and usually does divorce settlements but we can ask him about this and I’m sure he’ll be willing to get into the ring with an IP holder like Disney).

It doesn’t stop at cartoons. Movies, TV shows, video games, books, poems, paintings, music... if you want to use anything remotely modern, it’ll probably cost money. Sure, there are modern public domain works, but U.S. government creative works (automatically placed into the public domain), Python Software Foundation documents (explicitly placed into the public domain), and a handful of obscure creators are probably not your first choice for fifth grade reading material.

My sister, a grade-school teacher, ran right into this problem. She was looking for books for her class to read together, but the brutal calculus of Mickey Mouse’s 21st-century legal landscape does not hear your cries for mercy. Captain Underpants is a fun, popular book with an interest level around grades 4-8, but six bucks a pop multiplied by sixty students is $360. So each student can read one book. And guess what? They’ll need another book in a few weeks. The district budget won’t cover it, so are you in the mood to spend a few thousand dollars a year on books? Even if they last multiple years, do you want to spend a few thousand dollars once? On your job? Spend money. To work.

Um. No.

Readest thou yon book?

Project Gutenberg (PG) is an organization which aims to revolutionize literacy in the same way that their namesake did. Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century, allowing people to produce copies of documents by arranging metal blocks with the characters, applying ink, and then stamping them on as many pages as copies were needed, rather than writing everything out by hand. Project Gutenberg makes use of another technological breakthrough – Internet-connected computers – to gather copies of public domain works and make them freely available to anyone with an Internet connection and any device that can display text.

I’m a big aficionado of PG. I’d had a paper copy of The Three Musketeers for years, but when I finally got around to reading it, I noticed so many flagrant errors that I gave up on that edition and tried PG’s, only to find that it was equally messy. Both editions had typos, formatting problems, even entire missing passages... but not the same ones. So I started from the beginning, reading both editions in parallel while noting my corrections to the PG edition, occasionally looking for other editions online, translating from the original French when necessary, and even doing some research into French landmarks (the book takes place in the 1620s, but the characters spend time at a fort that was only built in 1672 – in fairness, the book was written in the 1800s). When I was done, I contacted PG and ended up with a producer credit for my work!

My sister needed cheap books, and I knew a website whose mission is accessible literature. Naturally, I recommended she browse PG and see if she could find something. She ended up going with Anne of Green Gables, published in 1908. Wikipedia notes that “it has been considered a classic children’s novel since the mid-20th century.” That’s a long time! Good thing children don’t change. And nor do people. Nor language. Nor the world.

My sister’s students found the book difficult to relate to. Small wonder, it being over a century old. Electricity is referred to exactly three times: twice as a novelty and once as a similie. The book is peppered with language that children are unlikely to understand, even with context clues: “ “The lady who keeps it is a reduced gentlewoman,” explained Miss Barry.” Reduced? Like sauce? Shortly afterward, a character makes a remark “with aggravating pity.” Good luck explaining that to a ten-year-old. They’ll definitely be interested in forging ahead once you’ve spent a few minutes clearing up that one.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying it’s a bad book. I skimmed a bit when picking out the above information, and the writing seems excellent. It’s just not Captain Underpants.

Grinding my gears down to perfect circles

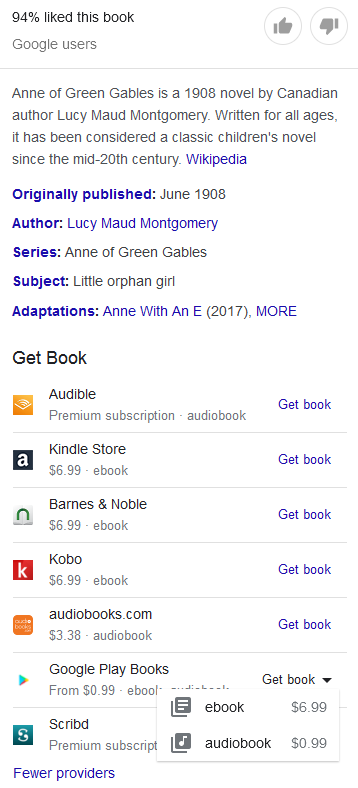

While researching basic facts about Anne of Green Gables, Google showed me places where I can get this book.

- Audible, premium subscription required (audiobook)

- Kindle, $6.99 (ebook)

- Barnes & Noble, $6.99 (ebook)

- Kobo, $6.99 (ebook)

- audiobooks.com, $3.38 (audiobook)

- Google Play Books, $0.99 (audiobook) to $6.99 (ebook)

- Scribd, premium subscription required (various formats)

Every single listed provider is charging money for this public domain book. I quite understand charging for the audiobook version; producing a new audio version takes time, talent, and effort. But... ebook? Seven dollars? Public domain? Charging money? Ebook? SEVEN DOLLARS? I’m angry at every single one of those sellers, and also at Google for only showing sellers and not showing any sites that provide the book for free. The first mention of a free source is PG’s version in the second page of search results. I’m angry, but not confused. A business that charges seven dollars for ebooks they didn’t write can afford to ensure that they are chosen by an “algorithm” wink wink to show up in a special box. I’ve even seen this sort of box tell me where I can watch movies and TV shows for free with ads, like Tubi or Pluto, but actual free stuff? Not in the cards, I guess. It’s like building a kiosk in front of a municipal water fountain and selling its water for seven bucks a glass. Sure, if you know there’s a water fountain there you can dig and eventually find it, but that should be the first option offered, not obscured behind parasitic megacorporate storefronts.

So that’s infuriating.

But anyway.

Childrens can learn

As a tutor, I’ve had my own experiences with teaching public domain books to grade-school children. Have you read Tom Sawyer? You can get a copy from Project Gutenberg on pretty much any device that can access the Internet and display text. Better yet, it’s a fantastic book. I can’t help but chuckle at the puns and silly scenarios sprinkled generously throughout; satirical scenes, like Tom convincing his friends that painting a fence is fun and they should do it for him, are still relevant today with e.g. social media sites relying on users to create content; Injun Joe is still a darkly unsettling villain.

But what does “lawn-clad” mean? As in, “followed by a troop of lawn-clad and ribbon-decked young heart-breakers.” They’re following “the belle of the village” into church, they’re also wearing ribbons, and they’re “heart-breakers”: they must be a group of young women in their nice church dresses. And to be “clad” in something means wearing it. So, they’re... wearing... lawn.

What is “lawn”? A patch of grass in your front yard? That’s the only definition used for that word today.

No. “Lawn” also means “a fine linen or cotton fabric used for making clothes” (Oxford Dictionary). Kids don’t know that. Adults don’t know that. Even I didn’t know that before encountering it here, and I’m a giant nerd. I suppose it was more commonly known in 1876, but I can very much understand why kids today will simply treat that sentence as one of many meaningless speed bumps that turn this novel into a struggle.

I understood that reference

Let’s look at an anachronism in Tom Sawyer that I did know without having to look it up first.

Tom keeps a pinch bug in a “percussion-cap box.” It is feasible for a modern adult to know what that is, but it’s a huge stretch. A key contributing factor to that divide is simply that this is about guns. Some people consider guns taboo and refuse to acquire any sort of knowledge about them, like learning that a box that stores ammo is called a magazine rather than a clip will turn them into a mass murderer.

Next, it’s archaic. Most people are familiar with the classic “kaboom” onomatopeia, but they may not know its origin. In many firearm lock designs (“lock” meaning the mechanism, as in a flintlock or matchlock), the bullet is propelled by a main charge of gunpowder, which is not ignited directly but rather by an intermediate fiery friend that gets set off by some other action, like an impact. Modern cartridges wrap everything up into a neat package, but guns using a “cap and ball” mechanism are fired by pouring a measure of powder into the barrel, ramming a lead ball cushioned by a patch of fabric onto the powder, putting a small metal cap over the nipple (located under the hammer), cocking the hammer, and pulling the trigger. The trigger releases the hammer which strikes the cap which ignites and sends a bit of flame into the barrel which ignites the main charge which propels the bullet. Phew! Did you catch that? Every time you fire a gun, you expend a percussion cap. So you need a bunch of them. They come in a box. And that’s a percussion-cap box.

Whether you read that whole paragraph or skipped ahead to here, I’m sure you’ll agree that a ten-year-old would definitely have tuned that out and started daydreaming about their crush. Pleasant, but not an effective way to get through a book.

For a dream that cannot be

Design patents (looks that don’t impact functionality) last 14 years. Plant patents (yes, you can patent new varieties of flora) last 17 years. Utility patents (devices, processes, mechanisms) last 20 years. Make something, patent it so everyone can see your design, have a reasonable exclusivity period where anyone who wants to use your work has to license it from you, and after it expires everyone can benefit from it. Innovators can profit from their work, but are expected to continue innovating at some point (unless they made so much money during the patent period that they don’t care to go on, but that’s neither here nor there).

Between Anne of Green Gables and Captain Underpants, however, lies a shadow world of “might have” media, that might have been public domain by now if not for Disney. With modern copyright terms, most individual works will retain copyright for a century or more. The copyright on a child’s fingerpainting could last for 150 years before falling into public domain. But, until 1976, the maximum was 56 years. At that point, anything still copyrighted suddenly got a new lease on life... and public domain froze. For napkin math, let’s say the term changed from 50 years to 100 in 1950. In 1949, then, works from 1898 and older were public domain. In 1950, only works from 1848 and older would be public domain, but everything from 1848-1898 already was. There would be no new works added to the public domain until the year 2000, a 50-year drought.

Of course, the actual system is more complex, with some works being the life of the author plus 70 years and other works being publication plus 95 or creation plus 120 (whichever is shorter – creating something and then sitting on it for 80 years before publication would only provide 40 years of copyright beyond that point). Thus, there will likely be errors in the following list of classic works that would have been public domain by now if Disney hadn’t done what they did. Keep in mind that this list only refers to characters and original appearances, not all derivative works. When Steamboat Willie (1928) and Mickey Mouse enter the public domain, Fantasia (1940) will still be copyrighted for another 12 years.

Movies

| Steamboat Willie | 1928 |

| All Quiet on the Western Front | 1930 |

| Frankenstein | 1931 |

| King Kong | 1933 |

| Bride of Frankenstein | 1935 |

| Modern Times | 1936 |

| Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs | 1937 |

| The Wizard of Oz | 1939 |

| Gone with the Wind | 1939 |

| Mr. Smith Goes to Washington | 1939 |

| Pinocchio | 1940 |

| The Grapes of Wrath | 1940 |

| Fantasia | 1940 |

| The Maltese Falcon | 1941 |

| Citizen Kane | 1941 |

| Casablanca | 1942 |

| A Streetcar Named Desire | 1951 |

| Singin’ in the Rain | 1952 |

| Shane | 1953 |

| From Here to Eternity | 1953 |

| James Bond | 1954 |

| Lady and the Tramp | 1955 |

| Rebel Without a Cause | 1955 |

| Invasion of the Body Snatchers | 1956 |

| 12 Angry Men | 1957 |

| Some Like It Hot | 1959 |

| Psycho | 1960 |

| The Magnificent Seven | 1960 |

| Spartacus | 1960 |

| Psycho | 1960 |

| West Side Story | 1961 |

| The Manchurian Candidate | 1962 |

| Lawrence of Arabia | 1962 |

| To Kill a Mockingbird | 1962 |

| The Sound of Music | 1965 |

Television

| The Ed Sullivan Show | 1948 |

| I Love Lucy | 1951 |

| Kermit the Frog | 1955 |

| Leave it to Beaver | 1957 |

| Lassie | 1958 |

| The Twilight Zone | 1959 |

| The Andy Griffith Show | 1960 |

Books

| John Steinbeck | The Grapes of Wrath | 1939 |

| George Orwell | Nineteen Eighty-Four | 1949 |

| John Steinbeck | East of Eden | 1952 |

| J.R.R. Tolkien | Lord of the Rings | 1955 |

| Harper Lee | To Kill a Mockingbird | 1960 |

| George Orwell | Animal Farm | 1945 |

| Joseph Heller | Catch-22 | 1961 |

| C.S. Lewis | The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe | 1950 |

| William Golding | Lord of the Flies | 1955 |

| Ken Kesey | One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest | 1962 |

| Ernest Hemingway | The Sun Also Rises | 1926 |

| D.H. Lawrence | Lady Chatterley’s Lover | 1928 |

| William Faulkner | The Sound and the Fury | 1929 |

| Virginia Woolf | A Room of One’s Own | 1929 |

| Aldous Huxley | Brave New World | 1932 |

| Margaret Mitchell | Gone With the Wind | 1936 |

| Vladimir Nabokov | Lolita | 1955 |

| Laura Ingalls Wilder | Little House in the Big Woods | 1932 |

| P.L. Travers | Mary Poppins | 1934 |

| Munro Leaf | The Story of Ferdinand | 1936 |

| T.H. White | The Sword in the Stone | 1938 |

| Ludwig Bemelmans | Madeline | 1939 |

| H.A. Rey | Curious George | 1941 |

| Esther Forbes | Johnny Tremain | 1943 |

| Astrid Lindgren | Pippi Longstocking | 1945 |

| Wilbert Awdry | Thomas the Tank Engine | 1946 |

| Margaret Wise Brown | Goodnight Moon | 1947 |

| E.B. White | Charlotte’s Web | 1952 |

| Mary Norton | The Borrowers | 1952 |

| Beverly Cleary | Beezus and Ramona | 1955 |

| Kay Thompson | Eloise | 1955 |

| Dodie Smith | The Hundred and One Dalmations | 1956 |

| Dr. Seuss | The Cat in the Hat | 1957 |

| Michael Bond | A Bear Called Paddington | 1958 |

| Margery Sharp | The Rescuers | 1959 |

| Norton Juster | The Phantom Tollbooth | 1961 |

| Roald Dahl | James and the Giant Peach | 1961 |

| Madeleine L’Engle | A Wrinkle in Time | 1962 |

| Stan and Jan Berenstain | The Big Honey Hunt | 1962 |

| Maurice Sendak | Where the Wild Things Are | 1963 |

| Norman Bridwell | Clifford the Big Red Dog | 1963 |

| Peggy Parish | Amelia Bedelia | 1963 |

But what about

Yes, I am aware of music! But the above are classics, not oldies, and the biggest problem with some of these old songs is preservation, not restriction. Generally speaking, music copyright mostly affects new artists who aren’t able to build on older works without fear of reprisal. “Happy Birthday To You” is the most egregious example, but even using a riff or sample from a song written in the 50s or 60s is fraught with peril because record labels compete with Disney for the title of most draconic soulless entity.

On the other hand, the band behind the “Amen Break,” one of the most widely-sampled and frequently-copied drum breaks ever, never got any royalties from it. The drummer died penniless and homeless, probably without ever even learning that his work was so popular. Published in 1969, it was popular by the 80s and 90s and is arguably the basis for entire subgenres. This unfortunate situation occupies the opposite end of the “copyright problem” spectrum: small, independent creators who barely even got credit, much less any profit, for work that has been included in thousands of tracks from other artists, to say nothing of how many times each of those tracks has been copied.

I also like video games. Yes, those count too. The reason they’re not listed is because most of them were published after 1964 (56+1 years ago), and titles that seem like ancient history from that dim dawn of gaming are just as copyrighted as anything else, even if their developers are unknown and their publishers defunct (known as abandonware, a term for orphan work specific to software or hardware). But it doesn’t have to be abandonware for even the shortest copyright terms to seem ridiculous; it’s all too common for publishers of well-known retro games to ignore a work for a few decades, rain cease and desist letters upon anyone who tries to acquire that out-of-print game and play it on an emulator during those decades, and then suddenly rerelease it on a modern console (on an emulator, of course) for the price of low-budget but still modern games (and then again on every subsequent console). The most infamous perpetrator of this offense is probably Nintendo, the Disney of video games. You can read my thoughts on emulators here. Basically, emulators are good and Nintendo is not your friend.

The situation might not get worse

According to this Ars Technica article, lobbying efforts peaked with SOPA and dwindled in the face of widespread backlash. Some big websites like Wikipedia blocked their own content with a message saying that the planned legislation was so bad that it would force them out of existence. And no one wants to lose Wikipedia; how would we do research? So apparently the current terms might actually last for a little while instead of freezing new public domain entries yet again. Works will be freely reproducible a mere 70 years after the author’s death, or 95 years after non-individual publications, or 120 years after creation! Assuming any copies of those works survived all that time!

Note that patents and copyrights aren’t the only IP protections. There are also trademarks, service marks, and so on. And Mickey Mouse is still a trademark of Disney. Effectively, I suspect that anyone gleefully reproducing Mickey and Steamboat Willie content in 2024 will probably end up being forced to cease and desist anyway.

Or the situation might get worse.

People are good at that.

List research sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Best_in_Film:_The_Greatest_Movies_of_Our_Time

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Best_in_TV:_The_Greatest_TV_Shows_of_Our_Time

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_novels_considered_the_greatest

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Monde%27s_100_Books_of_the_Century

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_children%27s_classic_books

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AFI%27s_100_Years...100_Movies

- https://entertainment.time.com/2005/10/16/all-time-100-novels/slide/all/

- https://entertainment.time.com/2005/02/12/all-time-100-movies/slide/all/