I like the smell of traditional books.— Bookworms

Emulators just don’t cut it.— Retro Gamers

For many, “the medium is the message” isn’t just the notion that media per se are a worthy topic of study – it’s a fundamental truth.

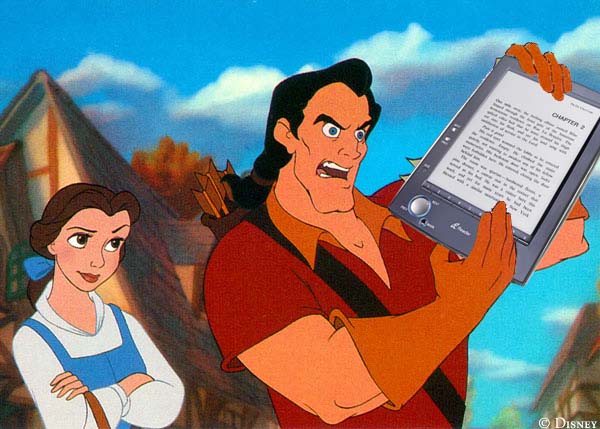

Ebooks

The entire sensory experience that accompanies reading a book – touching the paper, turning the pages, feeling the embossed cover art, smelling the pulp – has been integrated into the concept of “reading” in a sleight of meaning that would put a veteran politician to shame. It no longer counts as reading unless it involves paper and ink. Bookworms are then able to dismiss ebooks as some sort of imitation, like artificial flavors in a diet soda. “How can you read this?” they ask, turning an ebook this way and that. “It doesn’t smell like a tree.”

The logic goes like this:

- Reading is done with books.

- Books are necessarily made of paper.

- Ebooks do not contain paper.

- Therefore, ebooks are not books.

- Therefore, ebooks can’t be read.

- QED

This relies on a definition of “book” that includes a certain medium – viz, thin leaves of tree-based paper that have been covered in ink-based print, bound into a tidy stack, and partially wrapped in a material more durable than the leaves. Note how ebooks are already set apart by their very name: the addition of an “e” makes it easy to tell when someone is talking about these nasty, fake books. If today’s culture had seen the rise of ancient printing techniques, how would those techniques be viewed? Perhaps people would rebel against replacing papyrus with the sturdier, animal-based parchment, referring to parchment products as “cruelty books” or just “cbooks.” Given enough time with parchment, vellum products might not cause such a fuss, receiving the simple name of "vbooks.” In reality, of course, these techniques first appeared long ago, so they are now considered traditional to the point of antiquation (although vellum still sees some use). The ubiquitous paper book has been around for centuries, which, for many people, rounds up to “eternity.” This gives it a quasi-religious standing, especially in the face of heretical new teachings that threaten to displace or even replace it.

The world has seen the very same resistance to movable printed type: a soulless abomination that isn’t allowed in the same room as real books, because it wasn’t handwritten by a scribe. However, people eventually got used to the look of print, the scribes found other work, and the world became literate. Ebooks have similar potential: even the earliest ebooks put several volumes into the palm of your hand, and the state of electronic storage today allows you to hold an entire library in your hand, for the price of a few books. And, with efforts in the past few decades to make public-domain works freely available on the Internet, the cost goes no further. Rather than spending a fortune to fill an entire room with a small fraction of the works in the public domain, you can spend the cost of a family movie day or two to fill a handheld device with all of those works. As someone with experience in packing up and moving a family member’s personal library of nearly a thousand paper books, I can assure you that the magnitude of this change is absolutely enormous. The barrier to entry into a world of literature has all but vanished. With ebooks, we are fast approaching a world in which anyone can read to their heart’s content.

...Unless, of course, reading ebooks doesn’t count as reading. If not, one wonders what these purveyors of sin are doing when they stare at an ebook reader’s screen.

Over the decades, bookworms have also cited various technical shortcomings to bolster their ridicule of ebooks. Early attempts at ebook readers (the physical devices that display documents’ contents, which I’ll still refer to as ebooks) were almost comically awkward by today’s standards. A briefcase full of expensive electronics was a not a suitable replacement for an inexpensive paper book or two. The list goes on: awkward interfaces, poor battery life, low storage capacity, screens that caused eyestrain when used for more than a few minutes, slow response times... Compared to early ebook models, regular books are much more pleasing in many ways. Printing has been around for a pretty long time, and modern printed text is crisp and clear, but early ebook screens were low-resolution and low-contrast. To view more text in a book, you simply turn the page, a process that takes a fraction of a second. Early ebooks often required several seconds to replace the old page of text with a new one. Skimming through a book or navigating to an arbitrary page in a book can take barely a second if you know where to look, but seeking through an older or simpler ebook can be downright painful, with what amounts to a command-line console where you enter an exact page number – if you’re lucky. Of course, many ebooks include a search function, which can mitigate the need to seek through a document. The storage capacity of early ebooks wasn’t low compared to paper books, but people probably expected to hold more than four books in a device that cost $600. And, last but not least, battery life: you never have to plug in a piece of paper, but if you use an ebook, your book can run out of battery, much to the amusement of many bookworms. Of course, this witticism is never followed with a jab at the way a paper book can only ever display a single document, or the way it occupies over a dozen cubic inches of space to store barely a megabyte or two of data. No, there is no effort at a balanced picture. If your book runs out of battery, they’ll be too busy laughing to listen to anything else.

As for myself, I’ve been using ebooks since approximately 2001. My father gave me a Palm IIIxe that he no longer needed. This was a true Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), with alarms, calendars, an address book, a calculator, a notepad, and a few other essential apps for serious business types. Users input commands via a small plastic stylus. You could even get a folding keyboard for it (which I did) to bypass the quirky “Graffiti” handwriting recognition system. It was a computer capable of storing and displaying documents... which, of course, is all you need for an ebook, and that’s exactly what I used it for. The ebook ecosystem wasn’t as rich then as it is today, but I found some ebooks online (often with extensive OCR errors) and used the desktop application to transfer them into the device’s whopping 8MB of memory as memos or notes. Unfortunately, there was a rather low character limit for memos, so the ebooks were stored as a series of dozens of memos. Due to an implementation detail that would never have manifested if I had used the device as the designers intended, memos were sorted in reverse. The first one would contain the last few pages of the book, the second would contain the previous few pages, and so on. To read a book, I would open the last memo, read through it, then pull out the stylus, scroll back to the top of the memo, press the device’s “up” button to access the previous note, scroll up to the top of that note, then continue reading, repeating this process until I arrived at the first memo.

That’s dedication, not insanity, thank you very much.

I may have had to scroll through ebooks uphill both ways back then, but not anymore. The situation has improved considerably, as the potential market and profit margins that ebooks represent is far too great to ignore. To sell books to the entire literate world, at a basically nonexistent per-unit cost, with a purchasing effort as low as tapping a screen, Amazon, Apple, and other giants will eagerly improve the ebook experience to the best of their abilities. Today, we don’t even need dedicated devices to display ebooks: since such a device is basically a portable computer that retrieves and displays documents, any device that fills these basic requirements (with a few concessions to interface and other niceties) will work just fine. As it happens, many people carry such a device with them wherever they go: the smartphone. You might as well call a smartphone a tiny laptop with a cellular program, or an ebook with an antenna and audio capabilities. Download an ebook reader app (for free, of course – there would be no reason for you to spend hundreds of dollars on the hottest best-selling titles if you didn’t have an app for them) and you’re set.

Granted, not all smartphones have a screen big enough to be comfortably used for ebooks, but the trend is toward larger screens which are almost as large as a paperback book. Battery life is doing well, too, as new hardware becomes more energy-efficient (the batteries themselves don’t improve very quickly), so displaying static text that doesn’t require constant network activity isn’t much to ask of a smartphone. Capacity is more than sufficient, but it’s easy enough to just take a couple seconds to download a new book when you finish your current one. Smartphone screens are excellent, with one smartphone with a 3840x2160 (4k), 806ppi display already available. As a bonus, people already carry their phone wherever they go, so the convenience cost to having this ebook around compared to not having it is literally zero, whereas a paper book or dedicated ebook device is one more thing to tote around. This is perhaps the greatest single step to widespread acceptance of ebooks.

“Ebooks aren’t books! I’m not getting one.”

“You already have one.”

Emulators

Emulators have an even worse reputation than ebooks: they’re not just heresy, they’re theft. Briefly, an emulator (in the context of gaming) is a software simulation of a given console’s hardware. Users can then load a ROM (a copy of the game’s data) and play it on this simulated hardware. Since the machine running the emulator must be more powerful than the system it’s emulating, emulation is generally more popular for older games, which may have been released on cartridges into a world without widespread Internet use. With no copyright protection system and small ROM files, it’s all too easy to download an emulator for your favorite retro system and find a complete package of ROMs for every game in that system’s library.

The general argument for doing this revolves around the original producers’ inability to profit on a product that is no longer produced (sometimes the company isn’t even around anymore). But, with digital distribution, it’s becoming more and more popular to sell any given game multiple times. The game might have been produced in the 1980s, forgotten for twenty years, rereleased as a bonus feature or as part of a collection of older titles, ported to an online distribution system for a new console, ported to mobile platforms, and so on and so forth. These companies expect people to own a cartridge of the original game, then pay for it again when they buy the Mega Pack, then again for download to their Super Console, then again for Super Console Pocket. A single user may end up spending upwards of $100 to be able to legitimately play an ancient game that’s lucky to have half an hour of gameplay in it. At this point, I’m confused at what we’re buying: is it the physical copies and basic mechanical ability to play these games? Or do we pay for the “license” to play these games? This is similar to the mess of a music industry we currently have. Popular online services make it clear that you do not own the copies of the songs you bought, you merely own a license to use them on certain devices. But, if you experience a hardware failure and lose thousands of dollars worth of songs, you’re back to owning copies of the songs, and, just like owning a box of paper clips (or a video game cartridge), they won’t be replaced if you lose them. Until 2011, the Apple iTunes Store functioned exactly like this. It was a lose-lose situation for consumers: you weren’t allowed to protect your purchases by making backup copies, but Apple wouldn’t help you if something happened. At least with previous media formats (vinyl, cassette, VHS, CD, etc. and so forth) you could easily make a copy of your purchases just in case something happened to the original. Fortunately, Apple no longer follows this reprehensible practice, and purchased content can be downloaded to local hardware repeatedly.

In my opinion, companies should have to choose whether you are purchasing a physical copy or a license to play the game. If you are purchasing a physical copy, you should be able to do whatever you want with it for personal use, such as make a copy of it for more convenient use on other devices (like ripping DVDs so you only have to handle each disc once, ever). If you are purchasing a license to play the game, the status of your physical copy should be irrelevant. Lost a game disc? Experienced a hard drive failure that wiped out all of your games? Replacing the physical media so that you can once again exercise your purchased license should be cheap or free. If a company wants the authority to dictate licensing terms (you may use this game or song on this device, you may not sell it to a friend, you may not copy this disc, etc.), they should also have the responsibility of taking care of their licensees if something happens to the licensed product. The current condition is like a corrupt CEO demanding their share of the profits when a company does well but then asking for handouts when the company does poorly, or like a governing body banning the ownership of guns and then not providing emergency services.

So that’s why emulators often get the short end of the stick. However, recall that I mentioned that some of these game producers are long gone – for those titles, at least, the argument of “theft” is irrelevant and the argument of “authenticity” can come forward.

Shakespeare’s plays probably wouldn’t be any different whether he penned them on papyrus, parchment, or vellum, but, in the same way that the development of oil-based paint allowed for techniques and freedom that weren’t previously possible, video games are very heavily tied to the technology that surrounded their development. The limited graphics of the original NES were a heavy influence on Mario’s appearance, giving him a mustache instead of a mouth, overalls that clearly delineated his arms from his torso, a simple hat instead of hair, and a big nose. Modern games that rely on recent hardware would, of course, be impossible on older systems. No combination of circumstances could have produced Mario Kart 64 for the NES – the hardware environment is a real limit.

But, once a game has been released, how does a player’s decision to use a real console or an emulator interact with all of that? It doesn’t. Mario is going to have a charming, blocky sprite with a few bricks for a mustache whether you’re playing on a classic console or through an emulator on a modern PC.

How about the way the user experiences the hardware overall? The original Game Boy had a green-tinted, low-contrast screen with no backlight. If you held the system under a desk lamp, tilted it just so, and adjusted the screen’s brightness perfectly, you could play some fun games. The green screen was a part of that fun only in terms of its interference. The Game Boy Pocket, released after the Game Boy, had a sharp, high-contrast black/beige screen that was much easier to use. It was a fully-compatible Game Boy replacement – you didn’t have to buy a whole set of new games, or any kind of adapter. It was a lighter, more pleasant version of a Game Boy. When it was released, did hordes of retro gamers complain about how it ruined the experience? Nope! Firstly, “retro gaming” as it currently stands didn’t really exist at that time. Playing videogames wasn’t even called “gaming.” So,when a superior console was released, there was no outcry about how it’s just not the same if you don’t strain your eyes staring at a barely-passable screen. People who bought a Game Boy Pocket played the same Game Boy games as everyone else did. Was the experience different? Of course it was, but you can “experience” that green screen by playing any game at all on it for a few minutes. It’s a curiosity, nothing more. I guarantee that you won’t find any Game Boy game developers who were worried about whether their game would still feel right on the Pocket’s better screen, because of course it would. The old screen is different, but the new one is better. Nostalgia for irritation and discomfort can be satisfied with a brief taste, just to remember how bad it was.

Popular retro gamer personalities on YouTube like to loudly proclaim how they play everything on the original consoles, because emulators, of course, are unacceptable. They may not explain it any further than a vague reference to how it’s not “the same,” but they are firm in their beliefs. However, they will occasionally relent and recommend that interested viewers use an emulator to try games that are fun, but expensive (the most rare and therefore expensive games are generally the worst, because they are produced in low quantities, thrown away, or even recalled, while good games are mass-produced so that everyone can buy a copy). What do players lose when they go with an emulator? The YouTube personalities don’t add any disclaimer when they recommend an emulator. There’s no missing feature or content. It’s simply... not the same.

Maybe it’s the cables. Systems from the 1980s can be notoriously frustrating to connect to a television. The cables may be too short, or you may have to figure out an archaic RF switch box, or find a place for blade terminals. These were difficult enough to set up when those systems were new. Older gamers going for a taste of their childhood years may remember what to do (or what their parents did), but others will have to figure out for the first time an incredible mess that seemed normal at the time but in retrospect was probably the Devil’s handiwork.

Fun!

Fun?

Well, we used to deal with that on our way to fun, like the car ride to Disneyland. I can understand remembering those times and being nostalgic about them, but does anyone have fun reliving them? “Hop in the minivan, kids! We’re going on a ten-hour car ride like my family used to do when I was a kid! Here, have some RCA Phono Plug to F Jack adapters to play with! The time will fly by! No, of course we’re not going to Disneyland. This is the fun part.” Implausible.

Perhaps the YouTube retro gamer personalities are referring to the way old hardware will become finicky and eventually break down. I, for one, remember blowing at cartridge connectors in an effort to remove dust. Some of my old systems today are no longer reliable, requiring a few power cycles to actually load a game. It’s already become difficult to assure that they’re compatible with modern televisions – I recently discovered that my family’s television (a modern flat-panel) has no S-video input at all. I have no idea what would happen if I tried to plug in my ancient Sega Genesis. I still hang onto it, but I play its games via emulators or retro game bundles for newer systems. Cables, adapters, and switchboxes are nothing more than the implementation details that we used to be forced to deal with if we wanted to play these games, and I’m glad that they are no longer a requirement (although anyone who wants to relive that experience for its own sake is welcome to it).

Maybe they’re referring to the immense technical challenge of reverse-engineering a complex piece of electronics and recreating it in software as a hobbyist with no external funding or resources. Like any engineered product, emulators are susceptible to bugs. One emulator for a system may not have good support for gamepad peripherals, another may have sound glitches, and so on. However, better emulators are possible. Snes9x, an emulator for the SNES, is one such example. It’s probably the most polished, complete emulator available for any system. Perhaps if emulators weren’t the target of a broad smear campaign they would be in better shape. What if, instead of serving as just the right motivation for us to step up our efforts in the space race, the failures of Project Vanguard (the United States’ response to Sputnik) had convinced us that space travel was obviously ill-advised and not worth pursuing? In the same way that a failed launch doesn’t mean that space travel should be abandoned, a problem with a color palette in one emulator’s rendition of a game for one system doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with the underlying concept of emulation. Unfortunately, hecklers get caught up with what are nothing more than speed bumps and implementation details (or nothing at all, for emulators like Snes9x). More popular support for emulators would go a long way toward making them more reliable and ubiquitous.

The most likely explanation is that people who deride emulators and scoff at convenience are simply pretentious, and enjoy having something to feel superior about. This is, of course, perfectly valid. Everyone likes to feel special. However, that doesn’t mean that you really do need to play retro games on their original hardware. From a practical, objective perspective, playing a game on a suitable emulator is identical to playing it on the original console.

Conclusion

The medium isn’t necessarily the message. Ebooks are just books made out of something other than pulped trees. It doesn’t matter how they smell. You’re supposed to read them, not eat them or shove them up your nose. Emulators produce the same gameplay as hardware consoles do. Toggling a switchbox to channel 3 or channel 4 doesn’t make Mario jump any higher. You’re supposed to play the game, not analyze the hardware’s authenticity.

Ebooks and emulators will be refined continuously, growing in popularity until they and their enormous advantages are just as ubiquitous and highly regarded as digital photography. Perhaps one day, if humanity works very hard, new media will be greeted with enthusiasm rather than derision.

So go. Turn on a book.

And read.